The Story of Rare Books

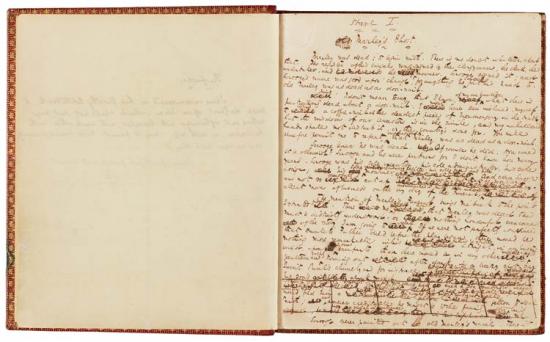

Manuscript of A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, 1843, at The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, New York. This page shows Stave I. Marley's Ghost. Page 1.

Last week I got to look at the following words in Dickens's own hand:

Scrooge closed the window, and examined the door by which the Ghost had entered. It was double-locked, as he had locked it with his own hands, and the bolts were undisturbed. He tried to say "Humbug!" but stopped at the first syllable. And being, from the emotion he had undergone, or the fatigues of the day, or his glimpse of the Invisible World, or the dull conversation of the Ghost, or the lateness of the hour, much in need of repose; went straight to bed, without undressing, and fell asleep upon the instant.

Some parts of the original manuscript of A Christmas Carol were crossed out and written over, but much of it was just as we read it today. He wrote it in only six weeks, starting in October and finishing in time for a Christmastime publication. His handwriting is confident and hurried, and the above passage in particular was hardly edited at all. He thought of these words. He wrote them down. Today this charming story is still just so.

It had been a while since a book had pulled at my heartstrings. I hit a dry spell in my reading this season. I can't remember the last time I encountered a writer that truly worked magic with words on paper alone. Perhaps it's my commitment issues with books, too many options, too often putting down pages to look at a distracting screen. Maybe it is the hazard of working with books as I do: At times they lose their romance and warmth. Selecting, invoicing, hauling them in boxes: Of course they occasionally feel more like the ordinary consumer objects than works of art, lessons to be learned, tales to be lost in.

Pierpont Morgan knocked me back to my senses with this 1843 manuscript in a glass case in his old library at Madison Avenue and 36th Street in New York City. He purchased this manuscript in the 1890s to add to what was, at the time, the most expansive private collection of art, artifacts, books and manuscripts in the world. In 1905 he completed the incredible building where these items are now housed. When he died, he left the collection to his son J.P. Morgan, with the intent that it would be made "permanently available for the instruction and pleasure of the American people." The Morgans' gift to the public was twofold: Today this incredible literary history is accessible through the open doors of Mr. Morgan's original library building, adjacent to his mansion. It is an architectural gem of its era, forever preserving the Gilded Age for one block of Midtown Manhattan.

Mr. Morgan's Library at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York City.

That a man named Charles Dickens came up with the story of Scrooge and his three spirits is alone delightful, and it is that story that this collection of paper and ink has to tell, at face value. The text pulls me back into the plot I know and love, whether in this serif font on a screen or in the author's scribbling penmanship. That tale then made it to publication, made it to worldwide fame, to the countless films created from its plot and characters. It is a challenge to avoid some version on rerun, or at the very least a Tiny Tim pop culture reference, every December. It became a cultural hallmark of Christmas (bah, humbug). In its particular flavor, with its English darkness and cheer, it became one of our more memorable fables. I never tire of its lesson of living with generosity and love. It tells us there is always time to change who we are. Consider, it instructs us, what might have been, what might be, what will happen. But also know that it is never too late.

Seeing this manuscript brought me back to that story, the intended one, but also told one with many more layers, turns and mystery. Manuscripts remind us of the literary context, the professional path, the daily life and creative energy of writers we hold dear. First editions, the first version of a book released in print, also have this power. In addition, they beg us to imagine the first readers to encounter a story. They speak to the path this copy of the book and The Book, the title in all its forms, took to a greater readership and to lasting notoriety. With a first edition in hand, we are reminded of the ingenuity of storytelling, the project of bringing something to print, the risk and the potential of putting one's words in the hands of the public, the critics, a legacy of literature. In such volumes, we examine storytelling, and the technology of paper bound together, as they have been, as they are, as they will be (here Dickens's Christmas ghosts haunt again).

It was Dickens's daily life and the world to which be brought this story that I saw in his manuscript. Like coming across someone's grocery list or scribbled notes to self, but with far deeper implications. One imagines Dickens's mind, talent and style in the act, at the writing desk, pen in hand. I wondered at his need for cash flow in tandem with his desire to tell this narrative. I considered the editor that liked it (or not), the typesetter that put it on pages to be sold, the first readers to encounter the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come (decidedly the most daunting, haunting of the ghosts). It made me want to revisit the story and to learn more about its author. The presentation of the volume at The Morgan shows the legacy of Pierpont's consideration, 120-some years ago, perhaps a bit similar to mine, that this scribble-full notebook was a special way of exploring the tale further. One wonders at his vision for not only protecting that value, but in giving it back to the public to be inspired and educated as well. There in its glass case, it also becomes the story of the visitors every day who marvel at the pages, try to make out words, take photos. Or perhaps they were more astounded by the Bach manuscript, or the medieval Book of Hours, or any one of the thousands of gorgeous volumes one is surrounded by in the room. A book for every reader, and every reader his or her book, we librarians say.

One of three Gutenberg Bibles in The Morgan's collection.

Across the room from A Christmas Carol, at the entrance to this cathedral-like space, is a Gutenberg Bible. I had never seen one, have you? One could easily glance past it at the many illuminated manuscripts and not realize what is in front of you in this volume. These pages are the first of humanity's love affair with the portable printed word. They are the start of that story. The beginning of open access to information. The beginning of a market for books that would spread across the continent and then extend across deserts and oceans. Here is the start of a worldwide phenomenon: Tales, poems, music and art available to the masses. Education, entertainment, and enlightenment that could be carried in your hand. The introduction to a volume of literature large enough, shortly thereafter, that homes began to have a specially designated room called a library.

The most recent rare book I purchased for a client was a first edition of The Virginian by Owen Wister. Set on a cattle ranch in Wyoming, it is considered to be the first Western novel. I return home from New York to this small tan book, published in 1902, and see it anew: it was the start, from one man's experience with the West, of a literary genre. It created a framework for a certain sort of character and plot line that we are, today, so familiar with that it's hard to imagine that it didn't always exist. Mr. Wister could not have known, the day this book went to market, that it would become a bestseller, would be turned into a play and later a movie version every other decade or so, that it would inspire further stories. It has embedded a perception of the West and its cowboys into our culture, into how we see ourselves and are seen by the world. That is the story this small book has to tell, past its pages.

First edition of Owen Wister's The Virginian. Private collection. Pictured here with Buffalo Ballad and Art of the American Frontier. Painting: 'Madonna on the Prairie' by W.H.D. Koerner, 1921.

The Morgan Library will forever be on my must-visit list when I'm in New York. This week I return to my stack of somewhat-inspiring bedside reads. Surely one will soon rise to the top. Here is a story as well: these objects in my home are still precious to me, even though right now it's more en masse than singularly. Rather than obsession with a story right now, I enjoy the possibilities in the printed word on my shelves throughout my home. The options available to me even here in rural Wyoming are endless. There are too many to choose between in this house alone. I can hop on the internet and purchase a signed copy of the very first printing of Tender Is the Night, see the words as they were first read, the greater story of 20th century literature in my hands. I can download Ulysses and read it for free. Should such options still disappoint, my public library is the gem of Jackson Hole, and they will order me any book I'd like from anywhere in the country, should I want to read it. What a world we live in, where we can explore so many pages in a lifetime, and furthermore, know where they came from. How they were written and how they have impacted others. All of these angles inspire me in my work gathering the very best of the stories, as well as "stories of stories" when it comes to rare books. It's a pleasure to create libraries that inspire the reader, the browser, and anyone who loves to consider how books speak to who we all are in the history of human storytelling.

Mr. Morgan's Library.

You can look at the digitized manuscript of A Christmas Carol here in The Morgan's Digital Collection. The scans are incredible, you can even see the ink shadowed through the paper from previous pages. Note that the memorable first line "Marley was dead: to begin with" was written as it is and never changed. How long did he sit with that before going at it with his pen? The preface reads,

I have endeavoured in this Ghostly little book, to raise the Ghost of an Idea, which shall not put my readers out of humour with themselves, with each other, with the season, or with me. May it haunt their houses pleasantly, and no one wish to lay it. Their faithful Friend and Servant, C. D.

I, for one, am perfectly and pleasantly haunted by it all. Your faithful Friend and Servant, C.S.S.